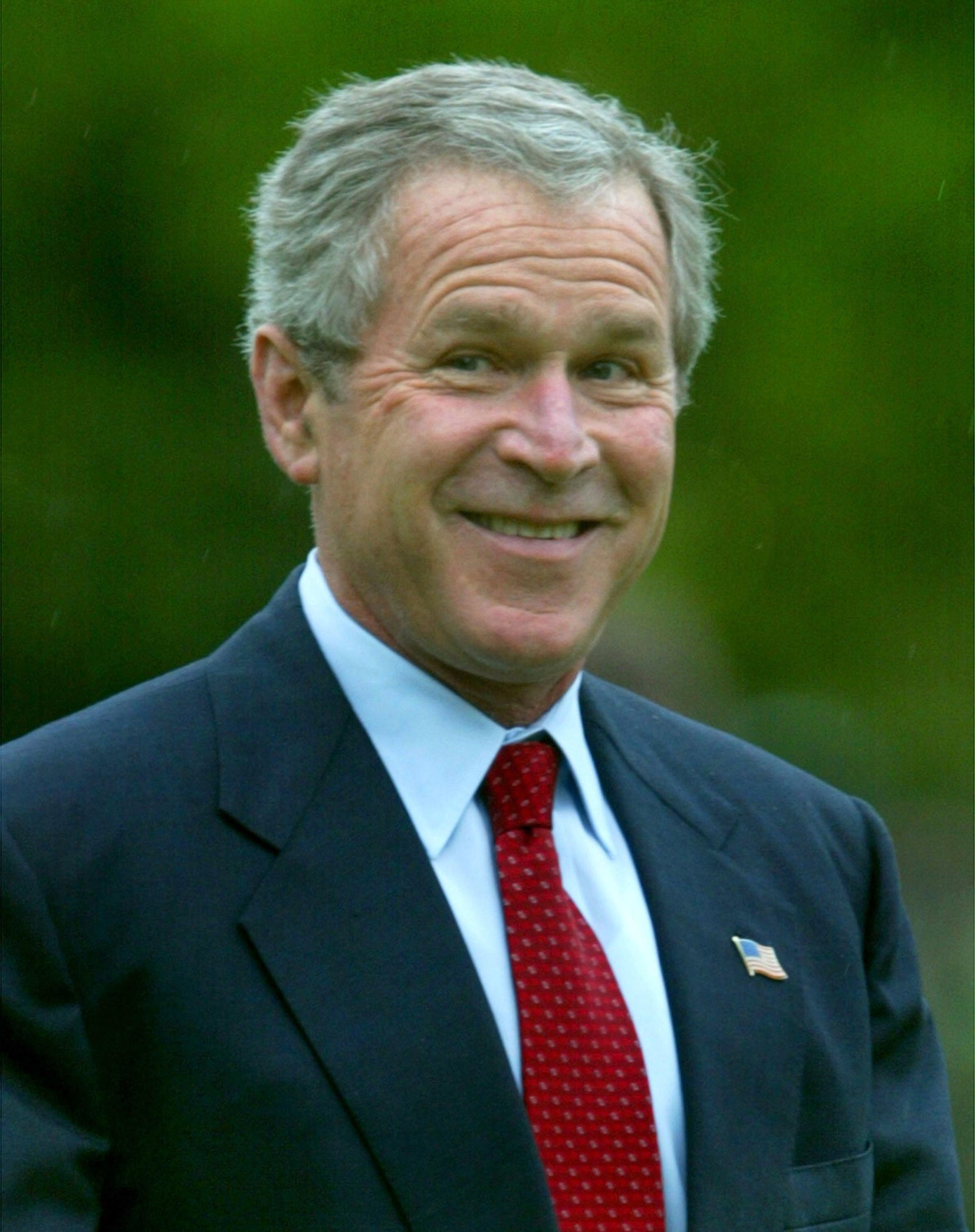

Titled "How the Bush Administration Pointlessly Screwed Over Student Borrowers" By Jordan Weissmann, Slate Magazine April 16, 2015

There has never really been a good reason to bar Americans from discharging their student loans in bankruptcy. Back in the 1970s, a spate of newspaper stories claimed that unscrupulous college kids and law school grads were borrowing money from the government without planning to pay it back, knowing that they could just go to court and weasel out of their debts before they had any real assets to lose in the bargain. But, unsurprisingly, the reporting turned out to be mostly anecdotal trash that was later debunked in a study commissioned by Congress.

Didn't matter. In 1978, Capitol Hill passed a bankruptcy reform bill that, for whatever reason, limited borrowers' ability to relieve their federal student loan obligations. Over time, lawmakers tightened the rules to make it even tougher.

A similar story more or less repeated itself during the Bush administration. Major private lenders claimed they needed Congress to stop their customers from filing opportunistic bankruptcies. Despite the notable lack of evidence that this was actually happening, lawmakers listened, and inserted a clause into the 2005 bankruptcy reform bill making private student loans nondischargeable unless someone could demonstrate they posed an "undue burden" on their finances—a vague standard which the courts have subsequently interpreted as an incredibly high bar.

So, was it worth it? Is there any sign, in retrospect, that the Bush bankruptcy bill needed to single out student debtors? According to a new working paper from economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, no, there is not. The researchers looked at how bankruptcy rates for private student loan borrowers changed after the reform bill went into effect, then compared them with the bankruptcy patterns for federal student loan borrowers and debtors without any education loans, who should not have been affected by the new law. If private borrowers had been filing for Chapter 7 in order to wiggle away from their debts pre-2005, you would expect their bankruptcy rates to fall significantly faster than they did for those without student loans or people who borrowed from the feds. That didn't happen, as shown on the graph below (see link)

"Although the 2005 bankruptcy reform appears to have reduced rates of bankruptcy overall, the provisions making private student loan debt nondischargeable do not appear to have reduced the bankruptcy filing or default behavior of private student loan borrowers relative to other types of borrowers at meaningful levels," the authors write. "Therefore, our analysis does not reveal debtor responses to the 2005 bankruptcy reform that would indicate widespread opportunistic behavior by private student loan borrowers before the policy change."

So the 2005 bankruptcy bill effectively made life a bit more miserable for hundreds of thousands of Americans in order to deal with an imaginary scourge. Worse yet, it may have encouraged the sort of risky private student lending that mirrored the subprime mortgage boom, with financial institutions shoveling debt at marginal students who were poorly positioned to ever pay it back but had no recourse in the bankruptcy courts.1

Now, there is some academic evidence that meeting the "undue burden" necessary to discharge student loans might be somewhat easier than the media has projected, especially if you're unemployed or have a medical condition. Princeton University Ph.D. student ________ has found that of all bankruptcy filers who have student debt, just 0.1 percent try to have it wiped out during the proceeding. But of those who do, almost 39 percent are successful. Of the more than 239,000 Americans with student debt who filed for bankruptcy in 2007, he believes there were about 69,000 who stood a decent chance of winning at least a partial discharge. More debtors need to at least give it a shot.

Still, discharge shouldn't take a special effort. The "undue burden" standard was unnecessary to start with. We'd all be better off scrapping the thing.

From the writer: Just to rant and rave about this at a little more length: In 2005, banks claimed that the nondischargeability rule was necessary to encourage more private student lending. But it is not at all clear that extra private student lending, especially to marginal students, is at all socially desirable. College students as a group are really bad borrowers. They default at high rates, in part because they often drop out of school. And while the federal government offers a number of forgiving loan-repayment programs that help troubled debtors, those protections are basically absent from the private sector. By eliminating dischargeability in bankruptcy, you're basically spurring banks to lend to high-risk individuals who have already maxed out their federal Stafford Loan limits (or, I should say, hopefully maxed them out, because there's no good reason for most students to pick a private lender over the federal government). I'm not sure who that's really helping.

There has never really been a good reason to bar Americans from discharging their student loans in bankruptcy. Back in the 1970s, a spate of newspaper stories claimed that unscrupulous college kids and law school grads were borrowing money from the government without planning to pay it back, knowing that they could just go to court and weasel out of their debts before they had any real assets to lose in the bargain. But, unsurprisingly, the reporting turned out to be mostly anecdotal trash that was later debunked in a study commissioned by Congress.

Didn't matter. In 1978, Capitol Hill passed a bankruptcy reform bill that, for whatever reason, limited borrowers' ability to relieve their federal student loan obligations. Over time, lawmakers tightened the rules to make it even tougher.

A similar story more or less repeated itself during the Bush administration. Major private lenders claimed they needed Congress to stop their customers from filing opportunistic bankruptcies. Despite the notable lack of evidence that this was actually happening, lawmakers listened, and inserted a clause into the 2005 bankruptcy reform bill making private student loans nondischargeable unless someone could demonstrate they posed an "undue burden" on their finances—a vague standard which the courts have subsequently interpreted as an incredibly high bar.

So, was it worth it? Is there any sign, in retrospect, that the Bush bankruptcy bill needed to single out student debtors? According to a new working paper from economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, no, there is not. The researchers looked at how bankruptcy rates for private student loan borrowers changed after the reform bill went into effect, then compared them with the bankruptcy patterns for federal student loan borrowers and debtors without any education loans, who should not have been affected by the new law. If private borrowers had been filing for Chapter 7 in order to wiggle away from their debts pre-2005, you would expect their bankruptcy rates to fall significantly faster than they did for those without student loans or people who borrowed from the feds. That didn't happen, as shown on the graph below (see link)

"Although the 2005 bankruptcy reform appears to have reduced rates of bankruptcy overall, the provisions making private student loan debt nondischargeable do not appear to have reduced the bankruptcy filing or default behavior of private student loan borrowers relative to other types of borrowers at meaningful levels," the authors write. "Therefore, our analysis does not reveal debtor responses to the 2005 bankruptcy reform that would indicate widespread opportunistic behavior by private student loan borrowers before the policy change."

So the 2005 bankruptcy bill effectively made life a bit more miserable for hundreds of thousands of Americans in order to deal with an imaginary scourge. Worse yet, it may have encouraged the sort of risky private student lending that mirrored the subprime mortgage boom, with financial institutions shoveling debt at marginal students who were poorly positioned to ever pay it back but had no recourse in the bankruptcy courts.1

Now, there is some academic evidence that meeting the "undue burden" necessary to discharge student loans might be somewhat easier than the media has projected, especially if you're unemployed or have a medical condition. Princeton University Ph.D. student ________ has found that of all bankruptcy filers who have student debt, just 0.1 percent try to have it wiped out during the proceeding. But of those who do, almost 39 percent are successful. Of the more than 239,000 Americans with student debt who filed for bankruptcy in 2007, he believes there were about 69,000 who stood a decent chance of winning at least a partial discharge. More debtors need to at least give it a shot.

Still, discharge shouldn't take a special effort. The "undue burden" standard was unnecessary to start with. We'd all be better off scrapping the thing.

From the writer: Just to rant and rave about this at a little more length: In 2005, banks claimed that the nondischargeability rule was necessary to encourage more private student lending. But it is not at all clear that extra private student lending, especially to marginal students, is at all socially desirable. College students as a group are really bad borrowers. They default at high rates, in part because they often drop out of school. And while the federal government offers a number of forgiving loan-repayment programs that help troubled debtors, those protections are basically absent from the private sector. By eliminating dischargeability in bankruptcy, you're basically spurring banks to lend to high-risk individuals who have already maxed out their federal Stafford Loan limits (or, I should say, hopefully maxed them out, because there's no good reason for most students to pick a private lender over the federal government). I'm not sure who that's really helping.

Bankruptcy Wizard

Bankruptcy Wizard

Comment