April 27, 2012

Six years after the death of Christopher Bryski, a 23-year-old student at Rutgers University, Key Bank has agreed to forgive his student loan. But Bryski's family is not stopping there: It's now fighting to change the laws in the hope of sparing others the trauma it endured as lenders continued to hound it for payment on its dead son's debts.

Christopher Bysksi died on July 16, 2006, after sustaining a traumatic brain injury in a fall that left him in a coma for two years.

Because his father had co-signed his student loan from Key Bank, he was obligated to continue to make payments under the terms of the private loan agreement. He paid more than $20,000 of the $50,000 debt, coming out of retirement to make the monthly payments, according to Ryan Bryski, 34, Christopher's brother.

But Ryan Bryski, an Air Force veteran, said various lenders continued to call the family and ask to speak to Christopher, despite the family informing them of, first, Christopher's vegetative state, and later, his death.

Bryski said the family lawyer sent "threatening letters" to two credit card companies to put an end to the continual postal mail, always addressed to Christopher, and phone calls requesting payment. Bryski said the credit card companies eventually forgave those debts. And Christopher's student loan from Sallie Mae was forgiven upon his death, according to the federal lender's policies.

But Key Bank, which held the private student loan, ignored requests to pardon the loan, Bryski said.

On April 18, the family started a petition on Change.org after the online petitioning platform contacted the Bryskis. With a petition signed by more than 81,000 individuals requesting to "discharge" the student loan debt, bank executives reached out to the family on April 23 and a settlement was reached on Wednesday, according to Megan Lubin, communications manager at Change.org. Change.org was also behind the petition that got Bank of America to cancel its proposed $5 debit card usage fee.

"My family is very grateful for Key Bank finally contacting us and doing the right thing," Bryski told ABC News. "It's just unfortunate it took eight years and 80,000 signatures to get their attention."

Gerri Detweiler, credit expert with Credit.com, said the Bryski family's story is a "very comon occurrence." In July 2011, the Federal Trade Commission released guidelines around debt collection for those who have died.

"But it is guidance, not law, and it does not cover creditors collecting their own debts, as they are not covered by the FDCPA (Fair Debt Collection Practices Act)," she said.

The FDCPA of 1996 amended the Consumer Credit Protection Act to prohibit abusive practices by debt collectors.

Detweiler said of the proposals the FTC considered was a "cooling off period" after death before resuming collection accounts, but it didn't decide to implement that.

"That may need to be reconsidered," she said.

"First and foremost, we are so sorry for the tragic loss of Christopher Bryski," David Reavis, a spokesman for Key Bank, said in a statement.

The bank said that, by law, it could not comment on matters involving an individual client or clients, but that it "regularly and continually reviews its practices, policies and procedures to ensure they are aligned with best practices and a constantly changing environment.

"Going forward, we will evaluate any similar situation involving a deceased student with outstanding loans – and we sincerely hope there are none – on a case-by-case basis," the bank's statement read.

Though the family is relieved that its own ordeal has been resolved and a bill has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives proposing more transparency for families who co-sign loans, Bryski is still hoping for change in other areas of death and disability policies of financial service companies. The family has also set up a website to provide updates about some of these issues.

"I asked myself what my brother would do. If he had the opportunity to help other people even if it didn't help him, he absolutely would. He was always helping others," said Bryski. "It's unfortunate that we lost him so young."

The family contacted members of the House and Senate beginning in May 2009, and the late Rep. John Adler, D-N.J., responded and introduced the Christopher Bryski Student Loan Protection Act in 2010 before he lost his bid for re-election and died in April 2011. Although the bill, which requires private lenders to clearly explain the responsibilities of co-signers in the event of death or disability, passed the house unanimously, it did not make it to a Senate vote before the end of the congressional session. The bill has been taken up by Sen. Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J., and Rep. John Runyan, R-N.J.

Bryski said his family was "very grateful" for Runyan's and Lautenberg's work for his brother's bill, but he also hoped the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal agency created under the Dodd-Frank Act that began operating in July 2011, would step in to regulate three other areas not addressed in the bill. If left unregulated, Bryski told the CFPB these areas would "continue to place families and individuals in terribly vulnerable financial and legal situations."

One of these areas is the current inability of co-signers to consolidate the private student loans of an original borrower who has died or become disabled.

Bryski also hoped that private education lenders would be required to provide protection against the unconditional repayment of, or to forgive, private student loans, which is the policy of federal lenders such as Sallie Mae.

He also hoped families could be informed as to whether they are required to continue paying credit card payments in the event of a death of disability of the original borrower. He said he hoped credit card companies would be required by law to close a borrower's account upon receipt of permanent disability certification or death.

"Throughout our ordeal, regardless of physician justification letters or pleas for reprieve, [two] banks hounded our family for payment, regardless of the traumatic situation at hand," Bryski wrote to the CFPB.

"Having received proof of his incapacitation and death, they didn't get it," Bryski told ABC News, referring to his brother's creditors. "[Christopher] couldn't even talk. It's just unfortunate."

Rohit Chopra, Student Loan Ombudsman at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, can assist those with private student loans, whereas previously, those borrowers did not have a central agency to contact.

"Many believe that private student loans have the same consumer protections that federal student loans offer," he said. "We often hear about this misunderstanding and its negative impact on student loan borrowers.:"

Consumers can contact the CFPB for assistance either by calling toll-free or (855) 411-2372 by visiting www.consumerfinance.gov

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Department of Education will release a report on private student loans this summer that will discuss many of these consumer protection issues.

"In most cases, if someone dies with credit card debt, the only people who are directly legally responsible for that debt are cosigners or, in certain states, spouses," Detwiler said. "But if there is not someone who is responsible for the debt, the creditor will want to find out whether is there an estate from which they can collect. And that's where it gets tricky. That can be situational, and vary by state."

Often, family members don't know whether the creditor can try to collect from money or assets, or even a life insurance policy, left by the deceased, she said.

"Creditors want consumers to buy credit protection plans that would typically wipe out the debt in the case of death or permanent disability, but that may not be necessary," she said. "Family members may not even be responsible and there may not be an estate from which to collect."

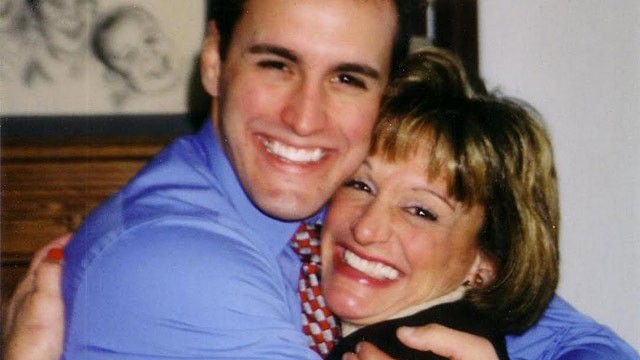

Christopher Bryski, pictured with his mother, Diane, died on July 16, 2006, from a traumatic brain injury. His private student loan was discharged six years later.

Six years after the death of Christopher Bryski, a 23-year-old student at Rutgers University, Key Bank has agreed to forgive his student loan. But Bryski's family is not stopping there: It's now fighting to change the laws in the hope of sparing others the trauma it endured as lenders continued to hound it for payment on its dead son's debts.

Christopher Bysksi died on July 16, 2006, after sustaining a traumatic brain injury in a fall that left him in a coma for two years.

Because his father had co-signed his student loan from Key Bank, he was obligated to continue to make payments under the terms of the private loan agreement. He paid more than $20,000 of the $50,000 debt, coming out of retirement to make the monthly payments, according to Ryan Bryski, 34, Christopher's brother.

But Ryan Bryski, an Air Force veteran, said various lenders continued to call the family and ask to speak to Christopher, despite the family informing them of, first, Christopher's vegetative state, and later, his death.

Bryski said the family lawyer sent "threatening letters" to two credit card companies to put an end to the continual postal mail, always addressed to Christopher, and phone calls requesting payment. Bryski said the credit card companies eventually forgave those debts. And Christopher's student loan from Sallie Mae was forgiven upon his death, according to the federal lender's policies.

But Key Bank, which held the private student loan, ignored requests to pardon the loan, Bryski said.

On April 18, the family started a petition on Change.org after the online petitioning platform contacted the Bryskis. With a petition signed by more than 81,000 individuals requesting to "discharge" the student loan debt, bank executives reached out to the family on April 23 and a settlement was reached on Wednesday, according to Megan Lubin, communications manager at Change.org. Change.org was also behind the petition that got Bank of America to cancel its proposed $5 debit card usage fee.

"My family is very grateful for Key Bank finally contacting us and doing the right thing," Bryski told ABC News. "It's just unfortunate it took eight years and 80,000 signatures to get their attention."

Gerri Detweiler, credit expert with Credit.com, said the Bryski family's story is a "very comon occurrence." In July 2011, the Federal Trade Commission released guidelines around debt collection for those who have died.

"But it is guidance, not law, and it does not cover creditors collecting their own debts, as they are not covered by the FDCPA (Fair Debt Collection Practices Act)," she said.

The FDCPA of 1996 amended the Consumer Credit Protection Act to prohibit abusive practices by debt collectors.

Detweiler said of the proposals the FTC considered was a "cooling off period" after death before resuming collection accounts, but it didn't decide to implement that.

"That may need to be reconsidered," she said.

"First and foremost, we are so sorry for the tragic loss of Christopher Bryski," David Reavis, a spokesman for Key Bank, said in a statement.

The bank said that, by law, it could not comment on matters involving an individual client or clients, but that it "regularly and continually reviews its practices, policies and procedures to ensure they are aligned with best practices and a constantly changing environment.

"Going forward, we will evaluate any similar situation involving a deceased student with outstanding loans – and we sincerely hope there are none – on a case-by-case basis," the bank's statement read.

Though the family is relieved that its own ordeal has been resolved and a bill has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives proposing more transparency for families who co-sign loans, Bryski is still hoping for change in other areas of death and disability policies of financial service companies. The family has also set up a website to provide updates about some of these issues.

"I asked myself what my brother would do. If he had the opportunity to help other people even if it didn't help him, he absolutely would. He was always helping others," said Bryski. "It's unfortunate that we lost him so young."

The family contacted members of the House and Senate beginning in May 2009, and the late Rep. John Adler, D-N.J., responded and introduced the Christopher Bryski Student Loan Protection Act in 2010 before he lost his bid for re-election and died in April 2011. Although the bill, which requires private lenders to clearly explain the responsibilities of co-signers in the event of death or disability, passed the house unanimously, it did not make it to a Senate vote before the end of the congressional session. The bill has been taken up by Sen. Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J., and Rep. John Runyan, R-N.J.

Bryski said his family was "very grateful" for Runyan's and Lautenberg's work for his brother's bill, but he also hoped the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal agency created under the Dodd-Frank Act that began operating in July 2011, would step in to regulate three other areas not addressed in the bill. If left unregulated, Bryski told the CFPB these areas would "continue to place families and individuals in terribly vulnerable financial and legal situations."

One of these areas is the current inability of co-signers to consolidate the private student loans of an original borrower who has died or become disabled.

Bryski also hoped that private education lenders would be required to provide protection against the unconditional repayment of, or to forgive, private student loans, which is the policy of federal lenders such as Sallie Mae.

He also hoped families could be informed as to whether they are required to continue paying credit card payments in the event of a death of disability of the original borrower. He said he hoped credit card companies would be required by law to close a borrower's account upon receipt of permanent disability certification or death.

"Throughout our ordeal, regardless of physician justification letters or pleas for reprieve, [two] banks hounded our family for payment, regardless of the traumatic situation at hand," Bryski wrote to the CFPB.

"Having received proof of his incapacitation and death, they didn't get it," Bryski told ABC News, referring to his brother's creditors. "[Christopher] couldn't even talk. It's just unfortunate."

Rohit Chopra, Student Loan Ombudsman at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, can assist those with private student loans, whereas previously, those borrowers did not have a central agency to contact.

"Many believe that private student loans have the same consumer protections that federal student loans offer," he said. "We often hear about this misunderstanding and its negative impact on student loan borrowers.:"

Consumers can contact the CFPB for assistance either by calling toll-free or (855) 411-2372 by visiting www.consumerfinance.gov

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Department of Education will release a report on private student loans this summer that will discuss many of these consumer protection issues.

"In most cases, if someone dies with credit card debt, the only people who are directly legally responsible for that debt are cosigners or, in certain states, spouses," Detwiler said. "But if there is not someone who is responsible for the debt, the creditor will want to find out whether is there an estate from which they can collect. And that's where it gets tricky. That can be situational, and vary by state."

Often, family members don't know whether the creditor can try to collect from money or assets, or even a life insurance policy, left by the deceased, she said.

"Creditors want consumers to buy credit protection plans that would typically wipe out the debt in the case of death or permanent disability, but that may not be necessary," she said. "Family members may not even be responsible and there may not be an estate from which to collect."

Christopher Bryski, pictured with his mother, Diane, died on July 16, 2006, from a traumatic brain injury. His private student loan was discharged six years later.

MAKE SURE AND VISIT Tobee's Blogs!

MAKE SURE AND VISIT Tobee's Blogs!

Comment